Transformation at the Intersection How public-private partnerships changed Pittsburgh into a thriving arts district

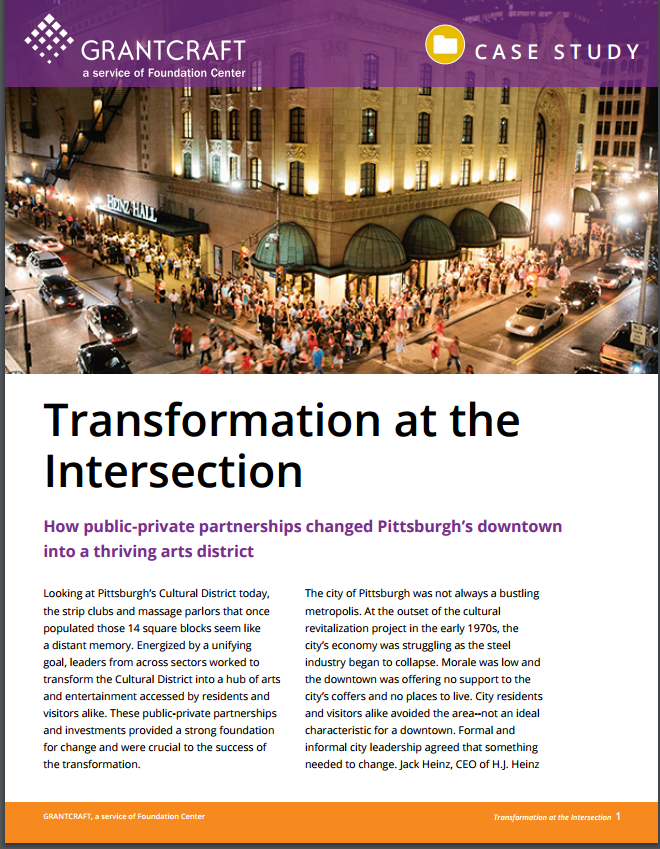

Looking at Pittsburgh’s Cultural District today, the strip clubs and massage parlors that once populated those 14 square blocks seem like a distant memory. Energized by a unifying goal, leaders from across sectors worked to transform the Cultural District into a hub of arts and entertainment accessed by residents and visitors alike. These public-private partnerships and investments provided a strong foundation for change and were crucial to the success of the transformation.

The city of Pittsburgh was not always a bustling metropolis. At the outset of the cultural revitalization project in the early 1970s, the city’s economy was struggling as the steel industry began to collapse. Morale was low and the downtown was offering no support to the city’s coffers and no places to live. City residents and visitors alike avoided the area--not an ideal characteristic for a downtown. Formal and informal city leadership agreed that something needed to change. Jack Heinz, CEO of H.J. Heinz and Company, longtime resident and civic leader of Pittsburgh, and original chairman of the Howard Heinz Endowment (which later became part of the Heinz Endowments), took the lead in mobilizing this effort. As Grant Oliphant, current president of the Heinz Endowments, says, the focus on the arts in particular played a pivotal role in the success of the transformation. “This town was on the verge of death,” says Grant, “and art is part of the story of what saved it.”

Visitors to Pittsburgh’s Cultural District roam the streets of the 14 square blocks at all times of the day.

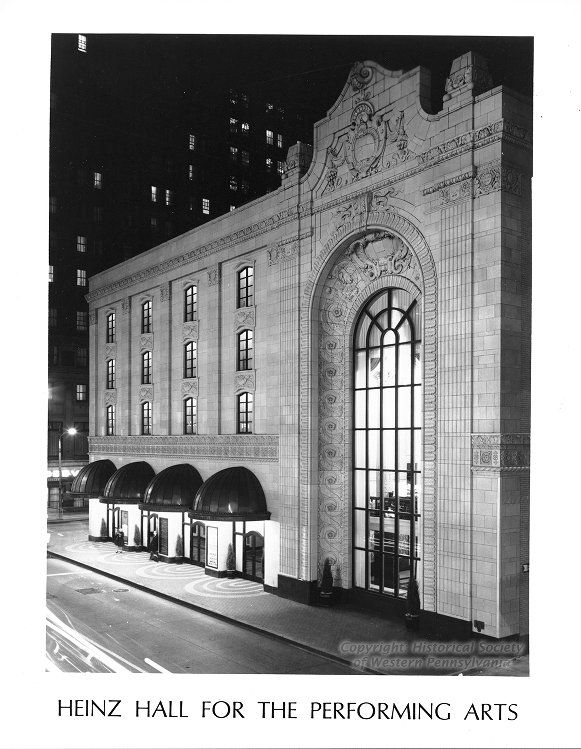

The Pittsburgh Symphony was the first domino in cultural revitalization efforts, as it very much needed a permanent performance hall. And so the metamorphosis to make Pittsburgh’s downtown a place that welcomed all residents began with the purchase of Loew's Penn Theater, which opened as Heinz Hall in 1971. While this gave the symphony a home, the location--in the middle of the red light district--was deterring traffic to the theater and preventing any expansion. Backed by the community, Jack Heinz put forth a daring plan: dedicate this entire neighborhood to arts and culture, and create a thriving area that citizens could enjoy. “He began to dream and dream of building a cultural district around Heinz Hall,” remembers Carol Brown, first president of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust which was created to act as an organizing and implementing entity throughout the transformation. “That was the beginning of our Pittsburgh Cultural District and the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust.”

Community-based leadership was an important aspect of this project’s success. “It matters in community change work that you have people in significant roles step forward and embrace their public visibility,” says Grant. Heinz was one of those people, as were the late Paul Jenkins, then president of the Benedum Foundation, and several other prominent philanthropic leaders, but in this systemic community change work, leadership is not a standalone changemaker. This initiative showed how philanthropy, public dollars, and corporate support all have a distinct and essential role. “The project was this wonderful melding of local government, state government, federal government, corporate dollars, and philanthropy,” notes Carol.

Accessibility was another important factor for successful public and private engagement. “What was unique about Pittsburgh and what made it an exciting place to be at the time, was the openness of the people, both in the public and the private sides,” says Robert Pease, then executive director of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development. “You could reach a CEO simply by making a phone call and they would step in enthusiastically to help solve problems.”

Government support of the Cultural District was profound and included a $17 million urban development action grant given in 1984, which helped fund the purchasing of property for development. Grant acknowledges that access to these financial resources is more limited now, but that governments at every level remain “the greatest sources of power and change.” He shared that the decision of Heinz and others to collaborate with government was in recognition of their unique power. “They have regulatory power. They can set policy, they can set regulations, they can drive practice in a certain direction.” In community change work, this can be a linchpin element to a project’s sustainability.

This urban development initiative also led to interesting collaboration opportunities between private and public actors. “When the Benedum Center Theater was being rehabilitated, we were able to get some federal funds by trading some air rights over that theater to the office center, so the office building could be built a little bit higher,” explains Robert. “Here was an interesting partnership that allowed for the success of the project.”

Corporate funding for a philanthropic vision can also be vital, as corporate dollars add to the needed pool of funds and leverage prominent household names to draw attention to that vision. The value proposition for a corporation is often different than calling upon the community loyalty and public responsibility that motivates private philanthropy and government funding. As Grant explains, “you have to make the case for why it’s in everybody’s best interest in order to gain support from all parties.” In this revitalization effort, corporate involvement provided another level of support. Corporations “bring stature, resources, and thinking to the table that is helpful to foundations trying to move a big agenda,” Grant adds.

Heinz Hall, the first building of the Cultural District.

With “one of the largest concentrations of philanthropic wealth in the country,” Grant explains that most of Pittsburgh’s philanthropic giving is community-focused. Private philanthropy was a large contributor to the project, and came from people living in the community. While Heinz was one such investor, the support of many other foundations, such as the Benedum Foundation, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, and the Buhl Foundation, was critical in making the project a success. “Heinz saw the importance of having partners in this type of work,” explains the late Paul Jenkins, former president of the Benedum Foundation. Grant shared that this involvement was largely inspired by the leadership’s ability to “leverage unusual loyalty” to the downtown region. Private philanthropy, unlike corporate and public actors, has flexibility to pursue projects outside of the traditional mold, while rallying support from all sectors. There are of course, limitations to working at the intersection of public, private philanthropy, and corporate influence, and Grant asserts that “the best partnerships are the ones where there is a clear alignment of interests” as this can help smooth over any bumps and ensure long-term sustainability. In the case of the Cultural District, there was a lot of engagement from all sides to transform the downtown into a usable, profitable, enjoyable space.

This transition to a functioning downtown was rolled out under the guidance of a master plan, which prioritized capital investments. The process was streamlined with the formation of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust in 1984, which acted as a vehicle to solidify and organize the overarching plans, coordinate between parties, and begin implementation. “I began to try to tell our story and to try to formulate a finite plan of how we would achieve this incredible goal,” shares Carol. “To do this we put together a team of planners that represented the cultural community, the public sector, outside consultants.” Grant explains, “Part of what Jack Heinz and the Cultural Trust did exceptionally well was to argue that for Pittsburgh to be a functioning, worthy city in an increasingly competitive national and global environment, it had to have a functioning downtown.” The Cultural Trust began to buy the property around the standing cultural buildings and for several years, these properties were held and rented until the Trust was ready to restore another building and fully absorb it into the District. This provided a source of revenue for the Trust, which it could then direct towards arts in the District. Thirty years later, the partnerships amongst sectors remain and help the Cultural Trust navigate their continuing plans for transformation. “This was a team approach,” says Carol, and it remains so today.

Then, as now, the plan for the District was not simply about renovating buildings, but was a holistic approach that addressed everything from green spaces to parking garages. “We needed things that would put people on the streets without having to buy a season ticket for the Symphony,” remarks Carol Brown. Art installations in pockets of grass mean that art is available to all, not only to those who walk through the doors of the theaters and galleries. Outdoor parking, rather than garages, encourages strolling the streets. The development of an apartment building in the area, that has been fully rented since opening, adds another element--the District is now a place people want to visit, and they want to stay. Comprehensive in its offerings, the District has something for everyone whether they be visitors to the city or Pittsburgh born and raised.

Today, over four decades after the outset of this project, the Cultural Trust still has plans to continue development, and is excited to carry on the work with intention. “This has been a 40 year process so far, and we’re not done yet. There’s still a significant chunk of the District to be converted from parking lots into something useful,” Grant says of the project. “I think this illustrates one of the core lessons of philanthropy: In this age of instant gratification, we need to remember that results at a meaningful level can take a long time. The role of philanthropy, not just as risk capital but as patient capital, is extraordinarily important.” In the future, Grant hopes that the Cultural Trust will eventually be able to go beyond the District to expand the impact of arts in Pittsburgh more broadly.

This ongoing effort to garner cross-sector support to strengthen the city will be most successful if truly everyone has access to it. Since the belief in art as a means of transformation, healing, and connection is at the core of the Cultural Trust’s values, it hopes to grow the accessibility of the District in the future for those residents who currently can’t visit the programs and spaces. “It's important not to neglect the cultural life of the community,” shares Carol. This mentality will hopefully allow for the benefits of the District and the arts to ripple even further out into the community, spreading positive change, because, as Grant states, “Art and creativity may be at the very core of what helps us survive hard times.”

This case study was developed as one of five companion pieces to stories shared through the Pittsburgh Philanthropy Project. The Pittsburgh Philanthropy Project, in association with the University of Pittsburgh, showcases the rich and varied narratives of giving in the region through comprehensive storytelling techniques, giving insight to the philanthropy landscape and approach for residents, researchers, and practitioners. Please visit storyline.gspia.pitt.edu to explore further.