Grantmaking for a Sustainable Future Lessons learned from Eden Hall Foundation’s unusual gift

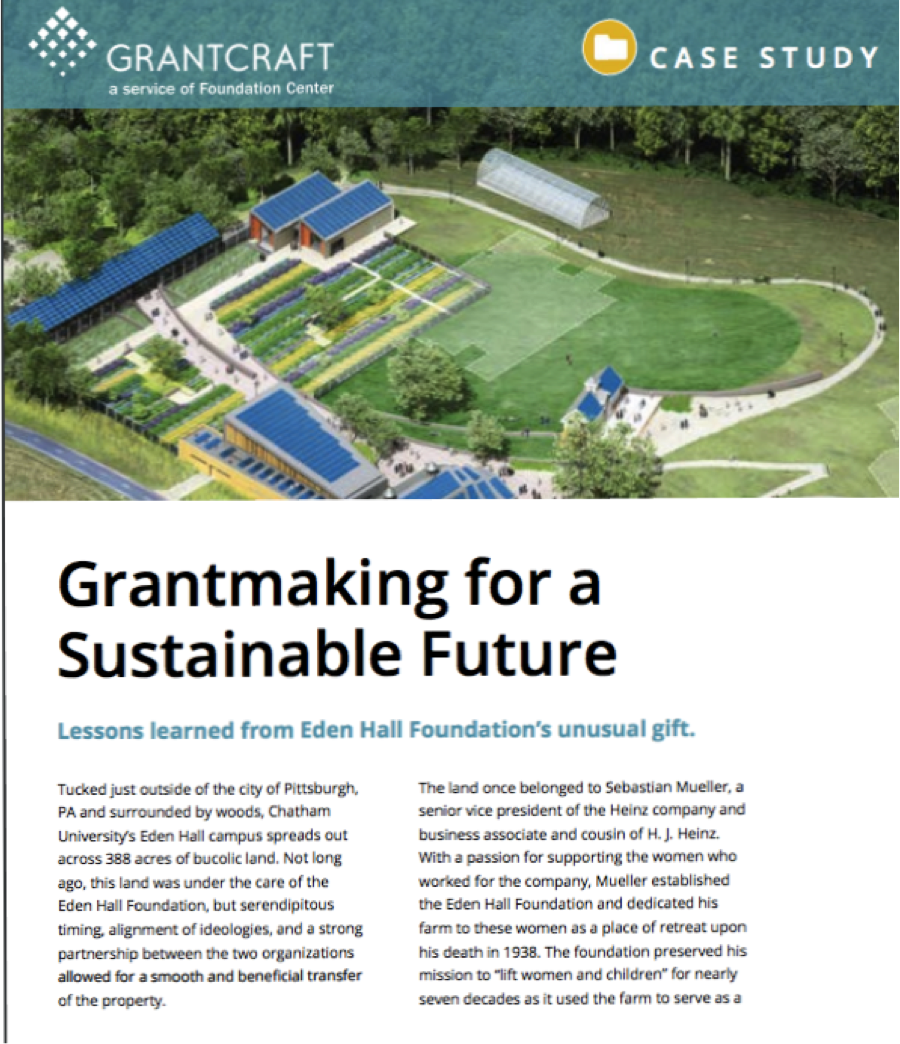

Tucked just outside of the city of Pittsburgh, PA and surrounded by woods, Chatham University’s Eden Hall campus spreads out across 388 acres of bucolic land. Not long ago, this land was under the care of the Eden Hall Foundation, but serendipitous timing, alignment of ideologies, and a strong partnership between the two organizations allowed for a smooth and beneficial transfer of the property. The land once belonged to Sebastian Mueller, a senior vice president of the Heinz company and business associate and cousin of H. J. Heinz. With a passion for supporting the women who worked for the company, Mueller established the Eden Hall Foundation and dedicated his farm to these women as a place of retreat upon his death in 1938. The foundation preserved his mission to “lift women and children” for nearly seven decades as it used the farm to serve as a prized space for women’s retreats. In 2008, as interest in retreats decreased, the foundation had an opportunity to shift with the changing times and make a new use of the farm through selling or gifting the land. Trustees wanted to make sure that the future owner used the land in a meaningful way, someone who could “move the farm forward” and use it to its fullest potential, explains Sylvia Fields, executive director of Eden Hall Foundation.

Intent on finding the right recipient and steward of the farm, Chatham kept surfacing in board room conversations. The university was historically an all-women’s school and alma mater of noted environmentalist Rachel Carson. When the foundation asked Chatham to share its future plans, it discovered that Chatham was, at the time, looking to expand and create a carbon neutral campus. Chatham’s vision for the land, combined with its commitment to women, captivated the Eden Hall Foundation. The foundation’s decision was sealed when learning more about two recent interests at Chatham: their “food and farm to table” initiative, and their plan to include a working farm at their new campus. Although the foundation considered a few development requests, it ultimately decided on Chatham and transferred the land to the university in 2008. “Everything was aligning. We really thought we were handing it over into good hands—the right hands,” says Sylvia. Chatham echoed this sentiment, notes Esther Barazzone, then-president of Chatham University. “We very much believed that we were the right institution to take this piece of land and that our historic mission to women in the undergraduate education and our great commitment to sustainability would mean that we would use this land properly.”

This gift of land illuminated an essential alignment between the foundation and the university. Most visibly, the interests of the foundation—namely fostering opportunities for women, sustainability, and connection to the land—squarely lined up with those of Chatham—offering education for women, sustainability, and environmental planning. Neither reframed its mission or objectives to match the other; the DNA of the two eventual partners were already intertwined. The timing was right; Chatham was looking for means of expansion and integration of strong environmental practices at the same moment that the foundation was ready to gift the land.

“We knew that Chatham was the right organization to receive this gift.” – Sylvia Fields, Eden Hall Foundation

As George Greer, an Eden Hall Foundation trustee, shared, “Chatham could afford to raise the money to actually put the property to use. It was clear that we couldn’t afford to support the property forever.” Local interest in sustainable food systems was increasing, signaling that the greater community would likely support the transfer and new use of the property under Chatham’s ownership. With a gift of this size and long-term impact, alignment of mission and timing, sustainability, and community support were essential. Sustainability was part of the equation, which was essential to long-term success. These factors laid the groundwork for understanding, buy-in, and the shared vision of the involved parties. Different missions, misaligned timing, or competing local priorities can often lead both recipient and funder to feel misled or disappointed—or there might not be a gift at all. In this case, the shared vision of Chatham University and the Eden Hall Foundation tells only part of the story. The gift would not have succeeded without an alignment in the grantmaking process itself, where both parties invested significant time and resources into analyzing the potential transfer and working together to imagine the most beneficial community outcome. The gift resulted from significant investment of time and a relationship-rich process.

Although the driving missions appeared to be in sync on the surface, the organizations spent time to collaborate, and, as Sylvia recalls, to conduct “due diligence to make sure that the visions were as aligned as we thought them to be.” Beginning the funder-grantee relationship with candid discussions regarding the fit allowed for both parties to feel comfortable with the grant and more importantly, for mutual trust to flourish. Eden Hall Foundation had been working with Chatham for a few years prior, helping to support some of their other initiatives. Because of this, the foundation staff had already connected with Chatham as a grantee. “Trust is something that you have to build over a period of time,” recognizes Sylvia, “it can start with smaller programs and observing how the partner handles the reporting and other unsexy things about a grant.” When trust on the part of the foundation is met by trust from the recipient that they will have agency with the gift, a strong relationship can form. “Chatham was stellar in being mindful of our needs, and this led to a great partnership, with a strong ability to work together and to trust one another.” The candor was vital in leveling power dynamics that are often at play, in that Chatham did not have to shift its narrative for the foundation or share anything less than its authentic vision. “Eden Hall Foundation gave us the gift of belief in what we can do and in our vision,” shares Esther. The result? A campus that not only benefits the students that attend Chatham, but contributes to the study and practice of sustainability in a global context.

For Sylvia, ensuring that an organization is prepared for a grant is also crucial to success. “Being ready,” as she puts it, “is good leadership, good clean finances, a vision, and a plan to get there. Chatham definitely was a very mature organization with a dynamic leader and a stellar board, and they were so ready.” For the trustees, this readiness was understood through open dialogue, clearly articulated plans for adopting new environmental practices, and demonstrated understanding of the foundation’s intent for the gift. In addition to being ready, Chatham was willing; they weren’t simply accepting the gift because it was offered, but the foundation saw how willing they were to activate the farm gift to advance the university’s mission.

“There are other ways to give in addition to writing a check that can be just as effective.” – Sylvia Fields, Eden Hall Foundation

Philanthropy is often thought of in terms of monetary transactions. But the story of Eden Hall Farm was not only non-transactional in its collaborative spirit, it was also nonmonetary. This doesn’t necessarily have to change the grantmaking process itself, as Sylvia says, because “even though it was nonmonetary, we still looked at it no differently than we would any other grant.” It highlights a broader scope of what can be considered a philanthropic resource. “I hope this story shows that there are other ways to give, in addition to writing a check, that can be just as effective. Nonmonetary gifts—such as property, such as time, such as talent—are viable options in a foundation’s giving sphere, and we saw the Eden Hall Farm gift as an important investment, like everything else.”

When the foundation made this land transfer, it was an investment in the vision of the university and how it would evolve its practices over time. The greater community of Southwestern Pennsylvania took note. Sylvia noted that “folks really sat up and took notice, and looked more closely at the university.” In fact, it inspired others to do the same, such as Sigo Falk, the former board chair of Chatham who went on to support the campus through his Falk Foundation to establish the Falk School of Sustainability. This gift also built on trust and alignment of mission and timing, demonstrating the ripple effect that a single thoughtful investment can have. The prominence of the university in the community and its dedication to environmental concerns will visibly elevate the work conducted on this land and through the Falk school well-beyond the campus borders.

For Chatham, the land offered the chance to expand in new ways and to strengthen its educational model. “This initiative will be a living and learning model in sustainability that we think will be of national importance,” shares Esther. For the foundation, the gift spread awareness in the philanthropic community that giving could be transformational and take nonmonetary forms. “Would I do it over again?” Sylvia asks herself, “In a heartbeat.” Now, Chatham’s Eden Hall Campus has a thriving farm, an interactive laboratory, and much more, and Sylvia, reflecting upon the new stateof-the-art campus says, “I have a great sense of pride every time I go out there.”

This case study was developed as one of five companion pieces to stories shared through the Pittsburgh Philanthropy Project. The Pittsburgh Philanthropy Project, in association with the University of Pittsburgh, showcases the rich and varied narratives of giving in the region through comprehensive storytelling techniques, giving insight to the philanthropy landscape and approach for residents, researchers, and practitioners. Please visit storyline.gspia.pitt.edu to explore further.